One of my favorite all-time thinkers is Douglas Hofstadter, Professor of Cognitive Science and Comparative Literature at Indiana University and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Gödel, Escher, and Bach, a classic in the study of consciousness with critical implications for artificial intelligence. In 2013, Hofstadter published a book entitled Surfaces and Essences with Emmanuel Sander where the two argue that “analogy is the fuel and fire of thinking”, a conclusion with which I could not agree more. So, recently, I have been looking for analogies and metaphors to help think about the investment opportunities related to generative AI. The one that keeps coming up in my mind is that of the gold rush and the embedded choice it presents to investors: do you invest in those selling the picks and shovels or in the miners prospecting for gold?

The lesson from real gold rushes is clear: at the beginning of a gold rush, invest in those selling the picks and shovels — let’s call them shovel shops for short — rather than the miners, which are usually a riskier bet, again, at the beginning. However, when dealing in the realm of software-based businesses, particularly cloud-based businesses, from Amazon, to Salesforce, to Uber, to TikTok, the economics and scale potential of cloud-based businesses can change the investment calculation. So, what does this mean for the gold rush of generative AI: shovel shops or miners?

The Gold Rush Metaphor. Let’s start with what this gold rush metaphor is trying to describe. Throughout history, we see many of these intense periods of innovation that spawn “compounding bounties of opportunity”. This is true of both companies and animal species. When looking for metaphors, sometimes I describe these periods as “Cambrian Explosions”, though that term might be getting a little overused already. Besides, I think I am going to reserve my Cambrian Explosion metaphor for a subsequent piece on the rise of cloud app platforms… Hint, just like in the real Cambrian, possession of “vision”, like possession of data, is a key to evolutionary fitness for most winning strategies, at least among the eukaryotes, I mean, the cloud-based businesses. I digress.

No, I think a gold rush is a good way to look at generative AI right now. Perhaps, there is some cultural bias here. Certainly, Americans often liken these periods of compounding bounties of opportunity, to gold rushes, over a dozen of which occurred during the 19th century in North America, most notably the 1849 California gold rush, from which the Levi’s corporation was famously born. Metaphorical gold rushes in business include the PC apps boom of the mid-80’s, the Internet party of the late 90’s, the rise of social media in the late ‘00’s, the mobile app explosion of the early ‘10’s, and the cryptocurrency craze of the late ‘10’s and early ‘20’s.

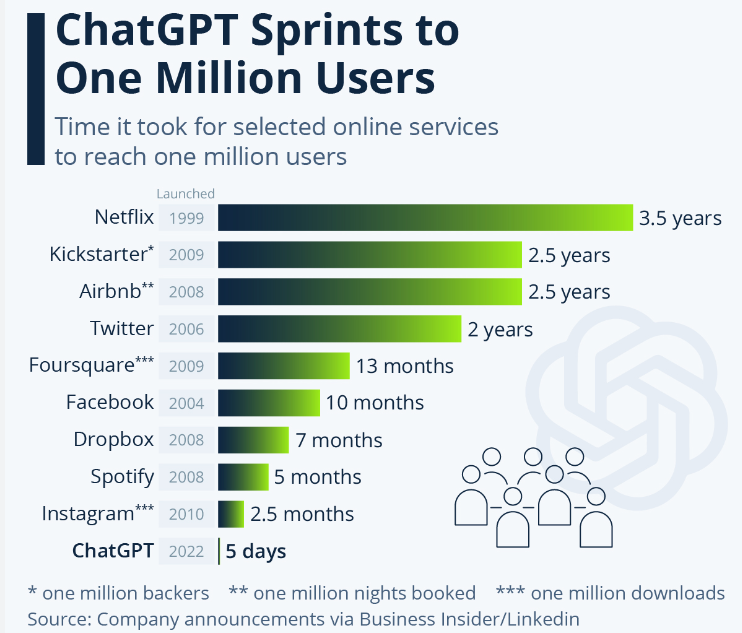

The comparison is not perfect. I don’t think “gold rush” quite captures the autocatalytic, “compounding” nature of these phenomena. Yet, it does capture “the fever” aspect, that feeling of an abundance of opportunity but with limited time to stake claims and break ground. Better hurry! There is a substantial FOMO or “fear of missing out” element to these gold rushes because it seems like more and more competitors are “rushing in” to take what’s left. Gold rushes generate a palpable sense of urgency, and, in the rush, it’s often tough to discern the once-in-a-decade opportunity from hype-driven head fakes. To stoke the FOMO fire even more, the innovation adoption rate continues to also increase geometrically for software-based businesses, with Chat GPT taking just five days to hit oner million users, compared with two and a half months for Instagram, as seen in the graph below:

That brings up another, less optimistic aspect of historical gold rushes that often represents the reality of these situations more generally: the vast majority of gold miners did not find their fortune and most gained little-to-nothing from the process. There were a few who did strike it rich, just enough and to such degree as to continue to fuel that “sense of rush” or at least store up surplus anticipation for the next rush. However, the big, repeatedly learned lesson is that the real winners from a gold rush were those who sold picks and shovels — or Levi’s jeans for that matter — to the gold miners. In other words, during these “gold rush” type periods when there is a seemingly open-ended set of emerging opportunities, the sure winners are those who supply the rushers as they try to strike gold. The basic logic of this investment strategy is, no matter who strikes gold, the key suppliers benefit, selling what is essentially competitive overcapacity to all of those willing to spend money to try and strike gold, even if that effort is irrational.

In 1995, with world wide web standardization complete, and triggered by the floppy disk proliferation of an easy to use “browser” made by a company called Netscape to navigate a growing number of “web sites”, we saw one of these “gold rush” periods with the rise of the Internet in the 1990’s. These gold miners – most were prospectors at this point — were called “dot.com’s”. Most were focused on e-commerce, using the Internet to sell some particular category of products, especially those with extreme levels of variety, i.e., with “long tails”. Books were the perfect long-tail category and, after Amazon staked its claim on “books mountain”, then, everyone tried to find the next “books” in order to be “the Amazon” of that new category. Others, like Yahoo, looked to Internet advertising opportunities, inspiring content start-ups where getting eyeballs that could be monetized in the future was everything and profitability, and sometimes even revenue, was an afterthought.

Let us set aside the fact that the equity bubble of the late 90’s was actually much more of a telecom bubble and not a dot.com bubble, the dotcom excesses have become canon for the “reversion to the mean”-ists, which have centered on the dot.com’s and the unrealistic expectations they generated. What is rarely pointed out is that, if one bought a basket of dot.com stocks in 1998, a basket that surely included AMZN, and held them until today, one would be up very close to ~1,640x vs. the S&P 500, which is up ~8x over the same time frame. That’s a difference in returns of over two orders of magnitude. By itself, an investment in AMZN through an equally weighted 30 stock dot.com portfolio circa 1997 smashes the investment returns of just about any benchmark one could choose. So, seen with a little time, the dot.com era wasn’t a bubble. It was one of the greatest buying opportunities ever. But you did have to make a bet on a gold miner basket, all of which surely contained AMZN.

Amazon: From Miner to Shovel Shop. What was behind the tremendous value creation that AMZN produced from 2001 through 2023? The question relates to a fundamental decision all cloud-based businesses have: which business strategy to pursue, gold miner or shovel shop?

Amazon was by far the most successful of the original gold miners from the mid-90’s1. So, let’s look at Amazon’s strategic path over the last two and half decades in terms of this mining analogy. In doing this, we’re going to slide back and forth between analogy and reality.

So, back in 1994, Jeff Bezos was one of many who anticipated the opportunities the Internet would create and the subsequent Internet gold rush the following year. So, he and his initial investors bought a bunch of picks and shovels and joined the thousands of other start-ups trying to strike gold in this newly discovered virgin territory known as the Internet. They selected a particularly good mountain to mine, selling books over the Internet, one with a very long tail that makes it ideal for mining in Internet territory. Mind you, Amazon could have pursued a shovel shop strategy and sold their software to bookstores. Instead, Bezos took the path of the gold miner and used software to become a bookstore.

This initial operation was wildly successful and subsidized Bezos’s expansion plans to mine the entire mountain chain of even larger amounts of ore in the semi-long tail of consumer products to sell over the Internet. The more Bezos mined, the greater scale benefits he gained over competing miners, many of whom were mining the old-fashioned way with a pan and a sieve in a stream bed of localized brick-&-mortar-based retail… just scooping out small amounts at a time at specific locations with ability to serve only a limited number of customers. Some mining companies are just huge armies of people with pans and sieves (say, Walmart circa 2000).

As mining operations continued to scale, Bezos saw that there was such a large variety of product category ore to mine that Amazon could not mine it all by themselves, but they could provide a platform for other 3rd party miners to use. That way, they could at least capture a part of a larger whole of transaction value, thus extracting maximum revenue from Internet territory. Essentially, what this is in the real world is matching the long tail of buyers, i.e., anyone with an Internet connection and a credit card, with a long tail of 3rd party sellers to maximize transaction volume on the platform.

At this point, Amazon’s mining operations had graduated from picks and shovels to become one of the largest purchasers of mining equipment from the world’s largest mining equipment vendors – i.e., Oracle, Microsoft, Cisco, Sun, and IBM. Yet, by the early 2000’s Amazon was even struggling with these off-the-shelf tools, which really could not handle the scale of mining operations Bezos was trying to pull off. You see, Jeff wanted to process entire mountain ranges full of various precious metals (i.e., a wide variety of data and transactions), but the even the most advanced mining equipment (e.g., Oracle databases limited to predefined schemas and SQL queries, or operating systems that are still tied to single CPU’s) were designed for relatively small, high-value rock and dirt processing requirements. They were not designed for mining Internet territory to become “the everything store”. By themselves, they would not do. Even his basic transportation, logistics, and supply systems (i.e., web server software and operating systems) needed to scale up (e.g., have one OS instance run across multiple servers) in order to even come close to mining all the opportunities possible.

If Bezos wanted to mine mountain ranges, he would need to build his own completely custom equipment, and, in order to do that, he needed to build an entire factory. So, Amazon built an entire “shovel factory”, Amazon Web Services, which was really built from scratch in order to make these specialized, automated, monster-size “picks and shovels” to mine the mountains for as much ore as possible. As it turned out, the factory Amazon constructed could make any type of equipment for mining or any type of construction, engineering, and public works projects in Internet territory.

Once it got up and running, it turned out that the sheer scale of the factory itself generated such excess capacity that it made sense to rent out that capacity to others so they could take advantage of the factory’s general purpose capabilities to produce a long tail of their own specialized mining equipment. It turns out that renting out space/time access to the factory was much more profitable than mining itself.

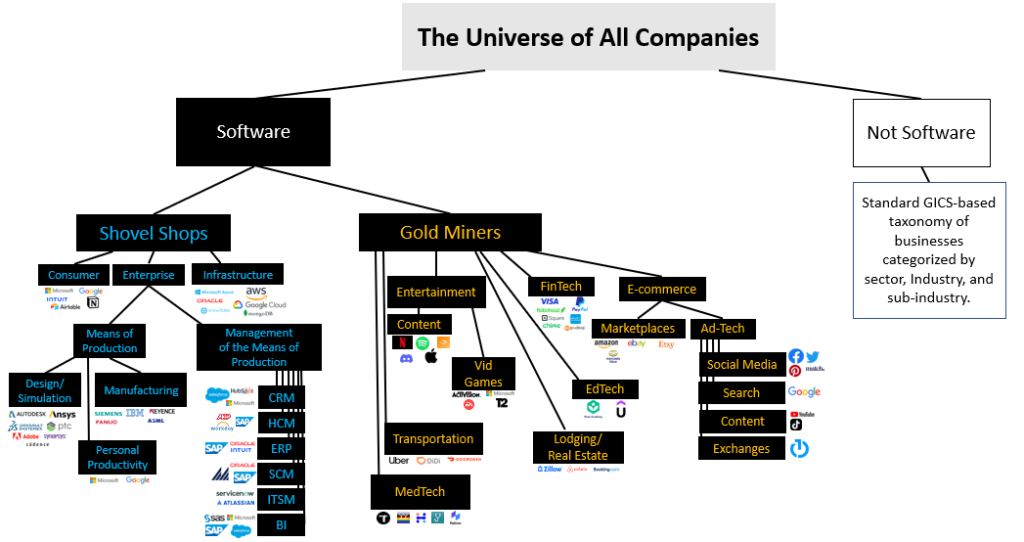

And now the business strategy circle is complete. Amazon is now a both a miner and a shovel shop, or more specifically, a shovel factory access provider… That is also now true for Alphabet and Microsoft, both of which are involved in search advertising (a form of mining) and cloud infrastructure services (a shovel shop). In fact, below is a map representing our take on dividing the world of software-based businesses into miners and shovel shops.

Click on image to drag and center and use mouse trackball to zoom in

The Shovel Shops of the Generative AI Gold Rush. While these analogies never line up exactly with reality, history seems to be rhyming with generative AI. Once again, there are two investment strategies for generative AI: miners and shovel shops. And, once again, we think it makes sense to invest in the shovel shops during this initial phase of market take-off. We think there will be massive winners on the infrastructure side as miners and the entire shovel-related supply chain sell into competitive overcapacity with those having the least replicable offerings being positioned best.

The shovel shops set to benefit most include nVidia, AMD, Micron, Pure Storage, and Arista Networks, not to mention the three main cloud infrastructure providers, Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, all of which will ingest and process orders of magnitude more data over the next three years as generative AI evolves and improves. Interestingly, all of these companies were big beneficiaries of the most recent gold rush, the “literally figurative” coin mining operations during the most recent cryptocurrency bubble. However, not all of them are necessarily good stocks to own from here. Valuation matters, even for the leader. Y’all know which one I’m talkin’ ‘bout.

Remember, Cisco was a great shovel shop stock in the 90’s, benefitting from two successive gold rushes: the enterprise network build-out, triggered by the proliferation of PC’s in offices and the value of networking those PC’s together, from the late 80’s through the late 90’s; then, the Internet and telecom infrastructure buildout from ’94 to ’01, which included the Telecom Reform Act of ’96, a key catalyst for the competitive build-out of overcapacity that was key for reducing network traffic transport costs. That over capacity hastened the advent of the commercial Internet and made cloud computing economically viable, which paved the way for what I like to call, the “comeback of miners”. Amazon and Google were not the only miners that struck it rich in Internet Territory after the infrastructure of the Internet was expanded and standardized for app-to-app data exchange. From that point, we saw a number of very successful miners take off: Facebook, AirBnB, Uber, Netflix, Snap, Twitter, TikTok, Reddit, Booking.com, PayPal, Etsy, etc.

The Case for Miners. So, investing in the shovel shops is not always the best investing choice in the face of such a powerful and influential trend. It’s just usually best at the beginning. See, at some point, if you get so good at making your own mining equipment and you know exactly where to dig, then maybe shouldn’t share your equipment and should become a miner instead. In some situations, miners can be great investments. Uber didn’t sell its software to taxicab companies. It became a taxicab company. Zillow didn’t sell its software to real estate agencies, it became one. AirBnB didn’t sell it software travel agencies, it became one, well, a type of one, kinda.With miners, there is often a twist on the old business model made possible by cloud-based software, a twist that takes a previously existing commercial function (e.g., travel agency) aggregates it, scales it, and makes it self-serve.

Of course, there are also companies, like Amazon and Alphabet, that pursue both models. , There’s the OG of miners and shovel shop hybrids, FICO, founded in 1956, with its Scores business (miner), where it uses its software to provide a credit rating service, and its software applications business (shovel shop) for use by others to develop their predictive analytical services, though usually for internal consumption to make better investment and marketing decisions.

So, history rhymes but it doesn’t really repeat. We believe the correct strategy for investing in the beneficiaries of generative AI right now is to bet on the shovel shops, but we also believe it makes sense to closely monitor selective miners as well. The big difference here is the velocity of adoption with generative AI. This time, a goldminer could get lucky much more quickly than was possible during the Internet Gold Rush, given the lightning-fast adoption we have seen of generative AI apps. Chat-GPT took five days to get to one million users and two months to get to 100 million users. By comparison, Netflix took 3.5 years to get to a million and 10 years to get to 100 million. That kind of fast broad adoption will make many miners quite rich, though we admit, it might be a little tough at the moment to figure out which ones.

So, we think it makes sense to keep a close eye on the newest use cases, even though gold miner candidates seem to be coming out on a daily basis. For example, when talking about winners from generative AI, Investors Business Daily recently published a very “pro miner” stance with an interesting example2:

[1] https://www.investors.com/news/technology/artificial-intelligence-stocks/

In general, look for AI stocks that use artificial intelligence to improve

products or gain a strategic edge. For example, Coca-Cola (KO) has

launched its new AI-inspired “Masterpiece” advertising campaign.

We think investing in KO to play generative AI is, well, a bit of a stretch. Nevertheless, thinking in terms of the miners and shovel shops is one of several metaphors we employ to sift through opportunities and make better investment decisions during times of compounding bounties of opportunity.