In August of 2010, I emailed the CEO at my former investment management firm with the idea that our style of long-term, concentrated, growth investing would be innovative in the Emerging Markets (EM) asset class. Over the next decade until I left in 2022, our firm built one of the leading EM equity funds in the world as measured by alpha (over 400 bps annualized since inception) and AUM growth (peak AUM in 2021 of $16b).

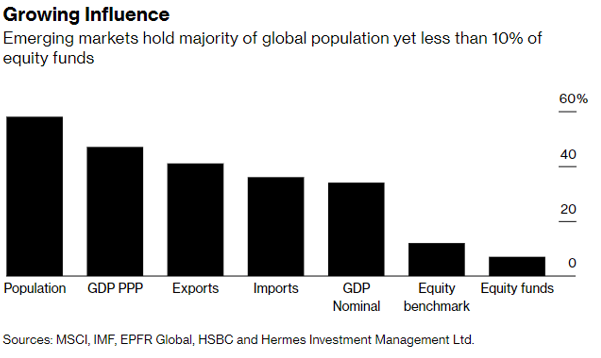

My colleagues and I were heeding the advice of market legends like Jeremy Grantham who advised young investors to take as much emerging markets equity risk “…as your career or business risk can tolerate.” We would show our clients charts like this from Bloomberg:

In short, we were as enthusiastic EM bulls as you could find. And of course, China was a big part of our success.

However, I now believe that we are at a moment where the EM asset class must be re-evaluated as a core part of allocator portfolios. The world has changed and global institutional allocators (pensions, endowments, sovereigns) will need to rethink the “China problem”.

Since China’s opening and reforms in 1978, it has been an economic miracle unlike anything we have seen, bringing hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, and rapidly ascending from an agricultural nation to the second largest economy in the world. My first personal interaction with China shocked me. I grew up regularly visiting India – my parents immigrated from India to the USA in the 1970s – and had expected China to look a lot like India. But when I visited Fuling, a tier 5 city featured in Peter Hessler’s fantastic book “River Town”, it was far more developed from an infrastructure and organizational perspective than anything I had seen in India. Over time, we have all heard stories about the fantastic airports and bullet trains across China.

There were at least two major implications for investors from the opening of China. First as China joined the WTO, it became a major buyer of global commodities and enabled countries like Russia and Brazil and other commodity exporters to get wealthier. China imported raw materials, used them to build its infrastructure and factories, and exported goods and deflation to the rest of the world for a couple of decades. Second, China started to develop a middle class and a consumer economy that became a force in its own right. Multinationals and domestic firms rushed in to serve this consumer and capture their share of the economic growth. China became a larger part of EM and global indexes and portfolios.

China’s rise and increasing wealth as it opened up drove the evolution of the EM asset class. Whereas EM investing started as a macro exercise practiced by currency traders and IMF/World Bank types, China’s ascension to the WTO sparked the commodity super-cycle (EM 2.0) and the rise of the BRICs (EM 3.0). Much of the commodity wealth that went from China to EM countries fueled the rise of the middle class in places like Brazil, South Africa and Russia. And as tech innovation diffused through the world, China looked to be the biggest beneficiary of EM 4.0, tech-driven disruption of every major industry and sector. But the actions of President Xi over the last few years have slammed the brakes on the EM 4.0 vision and are forcing a re-evaluation of EM and China investing.

On an almost daily basis, evidence is piling up that China and the USA will have a challenged relationship going forward. Last year, it was restrictions on semi-cap equipment companies selling certain types of IP to Chinese buyers. More recently, the world is recognizing that President Xi is playing by a different set of rules, and has solidified his stance of an aggressive China that will pursue its strategic interests with little regard for the global world order. This isn’t a new reality, but a continuation of a steady degradation in the relationship between China and the USA. For years, American companies like Google and Facebook have faced restrictions around domestic access to Chinese consumers. China has used its leverage to punish US brands and organizations like Nike and the NBA when it felt they were out of line. For our part, American regulators and legislators have gotten tougher too, using tools like tariffs to protect domestic industries; accounting/audit probes to force disclosure from Chinese companies listed in the USA; by going after Chinese companies like TikTok; bipartisan legislation calling out Chinese civil rights violations; and restrictions on investing into China for US federal retirement plans. This is only going one way and there is little evidence that it is going to change. So how should global investors and allocators deal with this?

First, investors should re-evaluate their EM allocations. EM is about 12% of the MSCI ACWI (All Country World Index) and many allocators have a similar allocation to EM within their equity portfolios. Meanwhile, China’s weight in the MSCI EM index has kept increasing (currently 31%) and will continue to rise as A-shares (local Chinese stocks) are included at higher weights. Russia’s exclusion from global markets also impacts the investible opportunity set. What’s left in EM is Taiwan, Korea, India, Brazil, and a handful of smaller countries (note: the FTSE EM index has already moved South Korea to developed status, making the China weight even bigger in that index). Investors should recognize that EM investing has become a “China” and “everything else” story, and often China is driving the entire EM complex. This is even more so for countries like Taiwan (14% EM weight) and Korea (11%) that are economically, culturally, and geopolitically linked to China. A broad EM index like the MSCI EM is actually much more China dependent on closer examination.

Secondly, and as a consequence of the above, allocators should evaluate their internal policy and risk appetite with regards to China exposure. Despite its current issues, China will continue to grow and create economic wealth and will simply be too important to ignore over the coming decades. But the Chinese exposure question has morphed from an economic one to a geopolitical and for some, a moral one. Would American institutions have invested in their biggest strategic rival during the Cold War? Each allocator will come to their own conclusions, but suffice it to say, it should be discussed and decided at the allocator level rather than left to an investment manager who serves many different allocators. Similar to an allocation to distressed debt or venture capital, the China allocation should be specified and quarantined.

Once the China exposure is decided, perhaps at half or a third of the prior EM allocation, allocators should examine what is left in EM, particularly if Taiwan and Korea are excluded because they are far too developed or too tied to China. These three combined are 56% of the MSCI EM. After that are India (15%) and Brazil (6%) and then a long tail of smaller countries. Once governance screens around state-owned companies and commodity/material restrictions are layered on, the EM opportunity set shrinks very rapidly. It may be the case that EM allocations should break up into China and Global Equity allocations to allow global managers to weigh the best businesses in India and Brazil against those in Europe, Japan and the United States. Global managers are best positioned to cherry pick the important companies from the remaining EM markets.

There are no easy answers here, but this is the most important topic in EM investing today, so it is a worthwhile discussion to have. Our view is that China and the United States will continue to have a challenged relationship for at least the next decade, and there will be flashpoints around trade and Taiwan that will make it very uncomfortable. The “China problem” has major implications on the EM asset class, and has moved into the realm of geopolitics which makes it more difficult to predict, analyze, and risk manage than traditional macro or company fundamental risks. Without China and China-linked countries, global allocators will have a very difficult time investing in EM – there just aren’t enough attractive places with enough liquidity. Allocators should proactively make a decision in the short-to-medium term rather than wait for an event that will force their hand, similar to how many of our hands were forced when Putin invaded Ukraine. Investors should strive for clarity around their China exposure and flexibility around their remaining EM allocations.

Finally, in future notes, we will explore some of the other important emerging markets to see if perhaps India can save the day, or if a resurgent Middle East may present investors with attractive opportunities.